The Renal Nutrition Group was the first specialist Group of the BDA and was formally established in 1970. A preliminary/informal meeting was held on 23 January 1970 at the King’s Fund Hospital Centre in London, chaired by Miss E. M. Booth, Chief Dietitian at Manchester Royal Infirmary. The main programme was devoted to the medical and dietary aspects of managing chronic renal failure patients treated by haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Later meetings would include renal transplantation and also conservative management.

It was decided during this meeting to approach the BDA to request they formally agree that the Renal Dialysis Group should obtain the status of a BDA Specialist Group as several other groups of specialist dietitians were also starting to organise themselves. The BDA Council agreed that the group should be named “Renal Dialysis Group” (RDG) although this was renamed “Renal Nutrition Group” (RNG) in 1997.

Membership, format and content of meetings

Three members of the RDG were elected for a term of three years to take care of the group’s administration and report back to the BDA and meetings were to be planned alternatively in London and elsewhere in the country. Fast forward to 1995 and the committee included a pre and a post registration education representative and in 2022 the Committee membership has now expanded to 14 members, including posts for project co-ordinators, post graduate education training and research lead, amongst others, to keep this speciality developing and provide the best experience for members

- Angeline Taylor (Bruno Mafrici outgoing) - Chair

- Sara Price - Secretary

- Shelley Wills - Treasurer

- Fiona Willingham - Audit, Service evaluation & Research Lead

- Joanne Pulman - PR

- Emma Taylor - Events Organiser

- Barbara Engel & Claire Gardiner - Post Registration Education Co-ordinators

- Katie Durman - Guidelines Lead

- Teresa Howes Katie Drake (outgoing) - Project Lead

- Shani Anderson - website & social media support

- Kathy Tsang & Elton Yu - Student representatives

Membership was initially restricted to dietitians working solely with renal patients, but from 1996 general dietitians could become members as it was recognised that many dietitians would look after CKD patients who were not on dialysis, and also job rotation had become integrated in workforce planning.

The BDA RDG mostly met for one day, twice a year since the early 1970s and the first BDA RDG meeting took place on 4th December 1970 and was attended by 36 dietitians. This meeting was also attended by Mrs Thomson, Chairman and Miss Jamiesen, Secretary of the BDA. Information regarding different treatment policies were obtained from the different Renal Centres and circulated in order to share best practice.

Members have always been encouraged to have an evidence based approach and the European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EDTA) Proceedings, 1968 and 1969,1 and the book Nutrition in Renal Disease; Proceedings of a Conference Held at the University of Manchester in June 1967 edited by Geoffrey Berlyne2 summarised best practice at the time. A review of this book3 stated that it included “normal protein requirements of man, aberrations of nutritional status which accompany renal failure and rational dietary regimes for the management of patients with chronic renal failure”. There were also sections on electrolyte and acid base balance, haematological complications, parenteral nutrition and paediatric care.

Working closely with the multidisciplinary team was also encouraged in order to enhance dietary compliance. The RDG meetings always included presentations by eminent nephrologists and other expert renal professionals to cover causes and treatment of advanced kidney disease and acute renal failure alongside national developments in nephrology and renal replacement therapy (RRT) including transplantation. Both Haemodialysis (HD)4 and peritoneal dialysis (PD)5 had been used experimentally from the start of the 20th century and ‘modern haemodialysis’ was stated to have started in the 1940s.4 The developments of the arteriovenous fistula (the Scribner shunt) and the Tenckhoff catheter in the 1960s led to better patient survival on HD and PD respectively, however the availability of these treatment modalities was still limited6 and current patients, now in their 60s, remember being told by their doctor (as a teenager) that they might not meet the strict criteria for receiving dialysis, and that the only other option was ‘conservative management’.7

Main recurring discussion points at present and subsequent meetings

Exchanging experiences by members was one of the most important topics during the 1970s and beyond, and RNG members undertook regular surveys of the whole membership to keep track of the current state of practice across the UK. This period saw many developments in new treatments and associated policy changes in management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) while dialysis and kidney transplant centres gradually opened to treat patients in renal units rather than home haemodialysis and PD also expanded.6 There was also a high turnover of dietitians, hence the RDG meetings were essential to focus on education of dietitians on these new developments and discuss teamwork between professionals as specialist nurses extended their roles in the management of renal disease.

Regular topics on the main programme agendas which had implications for dietetic practice were:

Conservative nutritional treatment

About 50% of centres prescribed the Giordano-Giovanetti (GG) Diet (20g high biological value protein including essential amino acids as a supplement and 2,000-4,000 kcal per day). 8 The GG diet had been developed in the 1960s, following the Kempner Rice Diet and the Borst Diet although the history of the low protein diet for renal patients dates back to the 1800s.7,9 It had been shown to reduce the mental, neuromuscular and digestive symptoms of renal failure as well as promote nitrogen balance10 and the ability to follow this diet was an indication of how well patients would be able to cope with the strict dialysis diet. Dr Berlyne (a renal physician based at the Manchester Royal Infirmary) had approached a metabolic dietitian to devise a suitable British version of the original GG diet. It consisted of 18-20 g high biological value (HBV) protein, 20 mmol Na including 1 egg, 1/3 pint milk and low protein food products such as wheatstarch and canned low protein (LP) bread. Methionine 500 mg in tablet form was prescribed as an amino acid supplement as well as B vitamins to support the very high carbohydrate content of the diet. Developing practical, acceptable menus for patients was essential to stimulate adherence to dietary treatment. Low electrolyte protein sources like K-LO in 1969 (dialysed egg) and Lo-Lek (dialysed milk) were available and also low protein bread, cereals, pasta were already available on prescription for patients with coeliac disease and PKU. Manufacturers were invited to develop canned salt free/low protein (LP) bread, LP cereal replacements for cooking and baking, and non-sweet glucose polymers. A range of products were available (Figure 1) and, together with 4 fl oz (100ml) double cream per day, were recommended to boost calories and prevent nitrogen wasting.

|

Low electrolyte protein sources: K-LO IN 1969 (dialysed egg) and Lo-Lek (dialysed milk) Low protein bread and cereals: Juvela bread and bread rolls, biscuits, mix: SHS LP starch-based products SHS, Carlo Erba Milano, Italy, Aglutella, GF Supplies, salt and salt-free Rite Diet LP bread, crispbread, flour pasta and recipes Welfare PKN Products Birkett and Bostock, Stockport, Cheshire Glucose polymers: Caloreen: Roussel, Maxijul Hycal Beecham: liquid glucose polymer various flavours Other: SHS/Nutricia: Duocal, Duobar, SnoPro, |

Figure 1: range of products available in 1970-1990 to boost energy intake

Diets were also carefully analysed and checked for vitamin and mineral content. Some evidence showed that patients felt their uraemic symptoms improved; however, compliance to a very strict diet was poor although many patients did follow these diets with support of their families, friends and the dietitian (Figure 2).

Following an international meeting on nutrition and kidney disease (held in Freiburg in 1973) scientific research had shown that improving the nutritional intake of renal diets prior to starting dialysis had a positive effect on improving malnutrition and improving outcomes. The renal diet was accused of “shrinking people to the size of their kidneys” and dietitians were aware that in order to prevent malnutrition and muscle wasting the energy content of the diet had to meet requirements. The GG diet continued to be prescribed for those that would not be selected for dialysis (eg. people over the age of 40) but gradually a ‘maintenance’ low protein (30g to 40g) diet was introduced as more renal units opened.

Dialysis diet

Dialysis sessions lasted between eight and ten hours, three times per week. Standard protein, energy and electrolyte (daily) recommendations for people on haemodialysis ranged between dialysis centres as follows:

Protein: 40-60g, sodium 10-80 mmol (no added salt diet; N.A.S), 40-75 mmol potassium, 2,000-4,000 kcal.

Fluid ranged from strict control of 500ml per day to 500ml plus urine output. The typical HD diet sheet would aim for 60g protein, 60 mmol sodium and 60 mmol of potassium with some units allowing dietary relaxation during the first few hours of haemodialysis, whereas the PD diet would aim for 80g protein, 80 mmol sodium and 80 mmol of potassium. Treatment aims for children on dialysis were protein 1.3-1.5g/kg with 100 kcal/kg but a free diet was allowed on dialysis, calcium and phosphate product was kept low.

A national survey in 1974 showed that units were starting to change their policies and 52% of units were increasing protein intake to 60g per day or more (although 35% were still following 0.6g protein per kg). Protein exchanges of 2g and 7g were advised, with 60% protein coming from HBV protein (7g exchanges). By 1982 a survey presented by Stella Agusiobo-Ifenu and Dr Pat Judd showed that only 11% of 45 renal units were prescribing a low protein diet (0.6g/kg body weight).11

To facilitate a very high energy intake some dietitians developed homemade high energy supplements such as the Renal Cocktail at the Royal Free consisting of eggs, double cream (150 ml), 100g Caloreen (a glucose polymer) and whisky. A supplement of essential amino acids was also sometimes continued in dialysis patients to cover dialysis losses.

Impact of renal diet: The cost of a renal/haemodialysis diet including high energy supplements, such as the recommended 4 fl oz (100ml) of double cream per day, was expensive for patients that were no longer able to work as a result of frequent and long dialysis treatment sessions. The Renal Dialysis Group and the Renal Social Workers Group approached the DHSS to assess supplementary financial support for CKD patients on a renal diet. However, in 1987 the DHSS stopped the special dietary allowance which dialysis patients were able to claim for the cost of their diets.

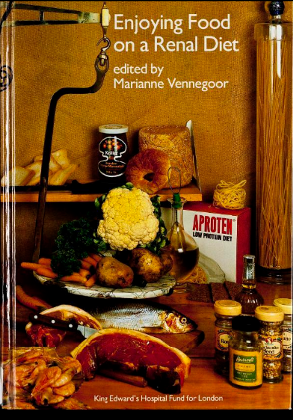

Resources: The Good Food and the Artificial Kidney cookbook was published by the Royal Free Unit at a cost of 8 shillings in 1970. The renal cookbook Enjoying Food on a Renal Diet (ed. Marianne Vennegoor) was funded by the King’s Fund in 1982. This book was a collection of favourite recipes supplied by patients and dietitians, which had been tried and tested.

In 1992 the 2nd revised issue of Good Food on a Renal Diet was published by Ultrapharm Ltd. The recipes were reviewed and adapted to include the current nutritional guidelines and using nutritional analysis programmes, not available previously. Also in 1992, the Exeter Renal Unit published the first set of videos for staff and patients, including dietary management and in 1994/5 diet sheets and audio tapes were developed for the Asian and Chinese Renal Patients by the renal dietitians from the Sheffield General Hospital.

Hypertension, drugs, sodium and fluid restrictions

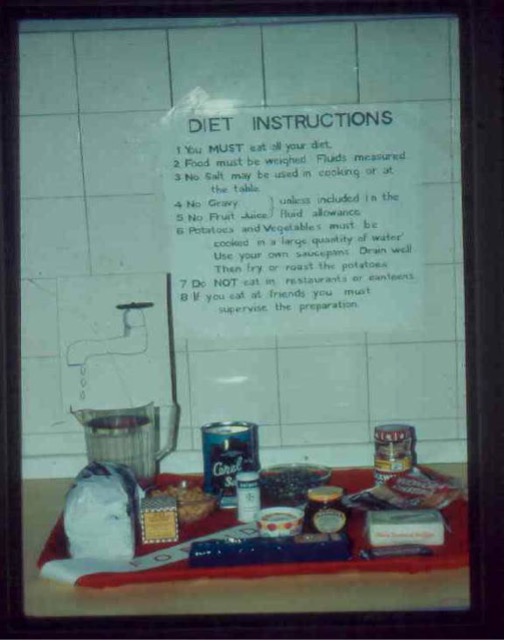

High blood pressure is a cause and consequence of renal disease12 and the renal unit kitchen at Middlesex hospital had this ominous poster on the wall indicating the strict nature of the dietary rules (Figure 3). In 1974, sodium prescription ranged from 22mmol to 60mmol per day (32% of renal units) to no-added-salt (N.A.S) (45% of renal units), although 19% said they did not restrict sodium. By 1982, dietary sodium restrictions were more relaxed with 36% (of 45) renal units stating they did not restrict sodium and no renal units stating they prescribed less than 40mmol per day.

Poster from Middlesex hospital diet kitchen

Renal osteodystrophy; dietary phosphate, calcium, phosphate binders (aluminium based) and vitamin D. A three-day symposium on renal osteodystrophy was held in 1968 and in the next five years there was an increased understanding of the role of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and vitamin D which was summarised in a symposium on divalent ions in renal failure.13 In the same symposium, Slatopolsky and Bricker14 described the role of dietary phosphorus restriction in the prevention of secondary hyperparathyroidism and, a couple of years later, the rationale for diet therapy in the management of bone disease was reviewed,15 advocating “provision of liberal calcium intake in the diet, appropriate restriction of phosphorus intake, provision of potent vitamin D analogs, and close attention to the calcium-phosphorus product”. G.M. Berlyne was also one of the first scientists to notice vascular calcification in the eyes of his patients and associate this with elevated calcium and phosphate levels.16 However, phosphorus restriction was not initially a feature of diet sheets while dietitians were still being cautious about protein intake. There was more awareness of decreasing phosphorus in the diet by early 1980s with 35% of units advising low phosphate diet, or at least avoiding high phosphate foods compared to 16% in 1974.11 Use of phosphate binders (aluminium hydroxide) had been introduced towards the end of the 1960s and in America the dietitians had produced recipes for cookies which contained crushed tablets. In the UK, phosphate binding agents (mainly aluminum-based) were being used in at least 70% of renal units.11

Hyperkalaemia, dietary intake and initiation of potassium exchanges. Hyperkalaemia increases mortality risk and dangers of this were noted in publication in the 1940s.17 Renal dietitians developed dietary information which incorporated potassium exchanges to differentiate between high, medium and low potassium foods and the fact that there are potassium losses during cooking. Patients were advised to soak potatoes and root vegetables overnight and double boil; bringing to boil then draining water and replacing before cooking fully. Dietary restriction for HD was initially a ‘blanket’ 60mmol/day and for PD 80mmol/day. American dietitians during this period were advising on 200-3,000mg per day (50 to 75mmol) on haemodialysis, with liberalisation on PD based on patients’ potassium levels. Interestingly, the survey of renal units in 198211 suggested that potassium restriction, although still a feature of diet sheets, was less of a priority with 22% of units not restricting potassium and it was noted in the RNG meeting minutes that the practice of double boiling of vegetables and potatoes to remove potassium would also remove the water-soluble vitamins. There were still concerns regarding the dangers of potassium and dietitians made calcium resonium biscuits and fudge for extended inter- dialysis time such as Christmas. By 1988 the recommended intake was based on body weight with a suggested allowance of “1mmol per kg ideal body weight spread evenly between meals”.18

Anaemia and iron supplementation. Erythropoietin (EPO) was developed by Amgen in 198919 but its use was rationed throughout the 1990s due to the cost of this treatment. Typically a patient could start dialysis with haemoglobin levels of 60g/l(normal range haemoglobin (Hb) concentration is 130 to 170g/L in males and 120 to 150g/L in females). Understanding the optimum dose of EPO and the optimum levels of haemoglobin have been the subject of much research over the past 30 years and this has developed alongside use of IV iron compounds.20,21 Although specialist ‘anaemia nurses’ tend to manage this aspect of patient’s treatment, the nutritional consequences of anaemia (tiredness, lack of appetite and taste changes, shortness of breath on exercise) are well known to the renal dietitian and a balanced diet is required to provide all of the nutrients needed to promote haematopoiesis.

Vitamin supplement and requirements to cover dialysis losses of water soluble vitamins. Low levels of the water-soluble B vitamins had been measured in HD and intermittent PD patients as early as 1963,22 although these patients were being maintained on a 40g protein diet.

From a questionnaire in 1989 sent out to 59 UK dietitians,23 34% of renal dietitians recommended vitamin supplements. There was a wide range of products available from individual vitamin preparations eg folate (Pregfol and Pregaday) to multivitamin products including water-soluble preparations ie orovite and ketovite. Problems with excess intake from iron containing supplements as well as fat soluble vitamins and hyperoxalaemia from excess vitamin C was already known, although low levels of vitamin C were also a concern.24,25 Vitamin supplementation had been free for renal patients on dialysis up to 1985 but was then withdrawn by the NHS. The renal dietitians approached companies that were able to provide renal dialysis specific vitamin supplements from the USA, i.e. Nephrovite. These products were imported and marketed by dialysis friendly companies like Kimal and later also imported from Germany (Renovit) and in 2000 by Unichem marketing Dialyvite at a reduced price.

Other hot topics included:

- Treatment of diabetic and elderly patients. As PD became more prevalent in the mid to late 1970s, the safety of this technique in older patients and people with diabetes was established.26 Scientific Hospital Supplies (SHS) established an annual award for one individual or a group of dietitians who submitted the best projects such as a publication, research or an educational tool and Caroline Hadfield from Portsmouth hospital won the award in 1986 for her paper, Nutritional care of Diabetic and Elderly Patients on Maintenance Haemodialysis.

- Nutritional assessment, parenteral and nasogastric tube feeding. Two surveys of renal dietitians were carried out in 1995: Role of Dietitians and Identifying Malnutrition and The use of Intra Dialysis Parenteral Nutrition. Simple and routine measures of albumin, BMI, weight loss and protein intake were shown to identify at-risk patients.27,28

- Psycho-social wellbeing of patients living with CKD on dialysis (dietary restrictions, cost of diet, frequent long dialysis sessions, fatigue and transport problems).

Training and professional development

Throughout the 1990s, the renal group developed post graduate training courses including; Conservative Management and Acute Kidney Disease (1990), Transplantation (1994) and Mature Returners Course (1995).

The Pre-registration Training sub-committee developed a Pre-Registration Pack for the renal experience of dietetic students in 1987. This was reviewed in 1997 and updated to include general nephrology and renal stone disease as well as CKD (latest version published online 2021).

Workforce planning

By 1991, the importance of renal dietitians was becoming clear with the Renal Association setting out what was required of a dietetic service. It was in this year that they published their paper Provision of Services for Adult Patients with Renal Disease in the United Kingdom on behalf of the Royal College of Physicians. This document was the start of estimating the renal workforce to treat the ever-increasing CKD population and stated:

“We provide below estimates of annual requirements for dietetic counselling. It is necessary to add time for record keeping, preparing explanatory and training documents, in-service training and communication with kitchen staff. Thus for a typical renal unit with approximately 200 patients on dialysis and 70 new patients per year, about 4,000 hours are required in all.

This is equal to two dietitians (Senior I) with assistance from a dietitian graded (Senior 2)

Requirements for Dietetic Services, per year:

New patients 1st year: 12 hrs/patients

Pre-dialysis after 1st year: 6 hrs/patient

Home and Centre HD and CAPD: 3 hrs/patients

Maintenance Haemodialysis: 6 hrs/patients

Acute ill patients: 52 hrs per inpatient bed

Nephrology clinic: 6hrs/patient on a renal diet”

In 1995 the Renal Association reviewed this document and members of the BDA-RNG contributed to a national audit survey of staffing levels in UK resulting in the advice to recruit 1 WTE for 135 all non-transplant patients and 1 WTE for 600 transplant patients.

Development of nutritional standards

The group has been instrumental in the development of nutritional standards for renal patients. In 1984, the Renal Dialysis Group published a national standards paper to update practice, based on a national survey amongst RDG members and on new evidence presented at the ISRNM Congress in 1982.

Best Practice Standards for Dietitians regarding the outcome of dialysis treatment were first introduced during 1991-1992 by the London Renal Dietitians Group. These standards were based on the National Kidney NKF HQFA recommendations in the USA and used by the NKF Council of Renal Dietitians. The National Guidelines for setting Standards of Dietetic Care for Adult Renal Patients project developed by the BDA-RNG was started in 1993 and finally published in 1998. In 1999 the RNG received the Elizabeth Washington Bursary award for the publication of the RNG document: Setting Standards and Achieving Optimal Nutritional Status: Standards for Adult Renal Patients over 18 years old.

Professional grading and regrading

In 1992 discussions took place to address the professional status of renal dietitians, especially as NHS Trust Hospitals developed. The grading of renal dietitians became an important issue regarding working conditions and contracts (originally only 50% were senior I level graded). In 1992, 81 dietitians were upgraded to Chief III when working with more than one dietitian working in the same speciality and graded Senior I.

Working with other scientific organisations

Alongside the development of the Renal Nutrition Group, national and international renal focused societies were being launched.

- Members of the RNG contributed to best practice guidelines produced by the Renal Association

- The British Renal Symposium (BRS) was formed in 1989 and a dietitian was invited to sit on its research panel

- The European Dialysis and Transplant Nurses Association (EDTNA) – Renal Care Association (ERCA) was formed in 19729 and the Journal of Renal Care has an impact factor of 1.585. The Renal Nutrition Sub Group was formed around 1974 and UK dietitians subsequently contributed to European Nutrition standards in the 1990s as many European countries did not have a developed dietetic service (edtnaerca.org/resource/edtna/files/EDTNA_ERCA_History_1971-2017.pdf)

- The National Kidney Federation (USA)/Council on Renal Nutrition (NKF/CRN) invited renal dietitians from the UK to become members of their organisation from 1985 onwards. The NKF led the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) in 1995 and produced guidelines which continue to inform best practice

- The International Society on Renal Nutrition and Metabolism (ISRNM) was formed in 1977 and the first renal dietitians from UK started to contribute at the congresses from 1982 onwards. In 1996 the ISRNM voted to include dietitians as associate members. From then onwards the society with the presence of renal dietitians has made a huge impact on nutrition and metabolic research and best practice for all renal professionals. One of the foremost journals focusing on renal nutrition, The Journal of Renal Nutrition (IF 1.724), is the official journal of the Society, published bi-monthly since 1991

Anniversaries

In May 1982, the RDG celebrated their 21st meeting at the Manchester RI with members discussing the past, present and immediate future of renal nutrition provision to CKD patients. Part of the programme was a display of dietary booklets, recipes and daily menus. Many delegates brought along their Modified G-G diet information and Miss E Booth gave her account of her experience of renal dietetics as a student.

In 1997 the RNG celebrated its 50th meeting with a special two-day meeting in Harrogate. Invited speakers presented an overview of the past, present and immediate future of dialysis and transplantation and a kidney patient talked about his personal experience as an HD patient of 25 years on haemodialysis. An exhibition included literature and samples of diet sheets, publications of recipe books and nutritional products developed from the late 1960s onwards. Many dietitians from the past attended and shared their experiences with the newly qualified renal dietitians.

Some original RNG members. Left to Right: Betty Sloan Edinburgh RI, Marianne Vennegoor, St Thomas London, Alison Finch, F Prygrodzki, Nottingham General Hospital and Sue Bennett, Leicester General Infirmary.

The review of the first 25 years of renal dietetics shows that renal dietitians were working closely with other experts in the field of renal medicine and were adapting dietary information based on medical advances and evidence of best practice from around the world. The developments which have taken place over the following 25 years of RNG history will be covered in the next issue of Dietetics Today.

Special Celebration Cake with BDA crest made by Mrs M Engel (mother of then Chairperson of RNG).

References

- European Renal Association. Dialysis and Renal Transplantation; Proceedings of the 6th Conference held in Stockholm Sweden June 1969 Ed Kerr D.N.S. https://www.era-online.org/en/edta-proceedings/volume-6/

- Nutrition in Renal Disease: Proceedings of a Conference Held at the University of Manchester on June the 29th and 30th 1967 Ed Berlyne G.M. Publisher E. & S. Livingstone, 1968

- Dower JC. Nutrition in Renal Disease, Proceedings of a Conference Held at the University of Manchester on June 29th and 30th, 1967. Am J Dis Child. 1972;123(3):265.

- Konner K. History of vascular access for haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005 Dec; 20(12):2629-35

- Phadke G.M. & Misra M. 2019 Historical milestones in Peritoneal dialysis in Ronco C, Crepaldi C, Rosner MH (eds): Remote Patient Management in Peritoneal Dialysis. Contrib Nephrol. Basel, Karger, 2019; 197: 1–8

- Williams B., Burton P., Feehally J., Walls J. The changing face of end stage renal disease in a UK renal unit. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1989; Apr; 23(2):116-20.

- Hensley MK Nutrition and Health: Nutrition in Kidney Disease Edited by: L. D. Byham-Gray, J. D. Burrowes, and G. M. Chertow. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ

- Berlyne G.M., Janabi K.M. & Shaw A.B. Treatment of Chronic Renal Failure: Dietary Treatment of Chronic Renal Failure. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1966; 59 (7): 665-67

- Di Iorio B., De Santo N., Di Iorio B, De Sato NG, Anastasio P, Perma A, Pollastro R, Di Micco L, Cirillo M. The Giordano-Giovannetti diet. J. Nephrol. 2013; 26(Suppl 22): S143–52.

- Giovanetti S., Maggiore Q., A low nitrogen diet with proteins of high biological value for severe chronic uraemia The Lancet 1964 May 9;1(7341):1000-3.

- Agusiobo-Ifenu S. and Judd P. Results of a survey into dietary treatment in renal units in the UK. Minutes of RNG meeting 1974

- MacGregor G.A. High blood pressure and renal disease. British Medical Journal 1977; 2: 624-26

- Massry S.G. Symposium on Divalent Ions in Renal Failure: Introduction. Kidney International 1973; August 4 (2): 71-72

- Slatopolsky E. & Bricker N.S. The role of phosphorus restriction in the prevention of secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic renal disease, Kidney International 1973; 4 (2): 141-45,

- Schoolwerth A.C. & Engle J.E. Calcium and phosphorus in diet therapy of uremia. J Am Diet Assoc. 1975 May; 66(5): 460-64

- Mallick N.P. & Berlyne G.M. Arterial calcification after vitamin-D therapy in hyperphosphatemic renal failure. Lancet 1968 Dec 21;2(7582):1316-20

- Keith N.M., & Osterberg A.E. 1947 in Clase et al Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney International 2020; 97: 42–61

- Tredger J. Watch the balance in renal failure. MIMS Magazine 1988, 47-48

- Kalantar-Zadeh K. History of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents, the Development of Biosimilars, and the Future of Anemia Treatment in Nephrology. Am J Nephrol. 2017; 45(3):235-247

- Macdougall I.C. Evolution of iv iron compounds over the last century. J Ren Care. 2009 Dec; 35 Suppl 2:8-13.

- Macdougall I.C., Geisser P. Use of intravenous iron supplementation in chronic kidney disease: an update. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2013 Jan;7(1): 9-22.

- Lasker N., Harvey A. & Baker H. Vitamin levels in hemodialysis and intermittent peritoneal dialysis. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 1963; 9: 51-56

- Sloan B. Results of a survey into vitamin supplementation. Minutes of RNG meeting 1989

- Sullivan J.F., Eisenstein A.B., Mottola O.M., Mittal A.K. The effect of dialysis on plasma and tissue levels of vitamin C. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 1972; 18: 277-82

- Wolfson M. Use of water soluble vitamins in patients with chronic renal failure. Seminars in Dialysis 1988; 1 (1): 28-32

- Heaton, A., Rodger, R.S., Sellars, L., Goodship, T.H., Fletcher, K., Nikolakakis, N., Ward, M.K., Wilkinson, R., & Kerr, D.N. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis after the honeymoon: review of experience in Newcastle 1979-84. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.) 1986; 293: 938 - 41.

- Harvey K.B., Blumenkrantz M.J., Levine S., Blackburn G.L. Nutritional assessment and treatment of chronic renal failure Am J Clin Nutr. 1980 Jul;33(7):1586-97

- Engel B., Kon P., Raftery M. Strategies to identify and correct malnutrition in haemodialysis patients J Renal Nutrition 1995; 5 (2): 62-66

- Wanner C. From WEDA to EDTA to ERA: 60 years of supporting European nephrology and counting. Clinical Kidney Journal 2022; 15 (8): 143-46