Ketogenic diets are well established in the treatment of children with drug-resistant epilepsy, and the evidence base is growing in their use with other conditions. Natasha Schoeler looks at how they can be used.

Medical ketogenic diets, or ‘ketogenic diet therapy’ (KDT), are a group of high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets used under clinical supervision to manage specific medical conditions. They aim to mimic the state of starvation on the body, promoting fat as the primary energy source through ketosis. KDT is different from purely low carbohydrate diets, which include varying amounts of carbohydrate (often over 50g/day).

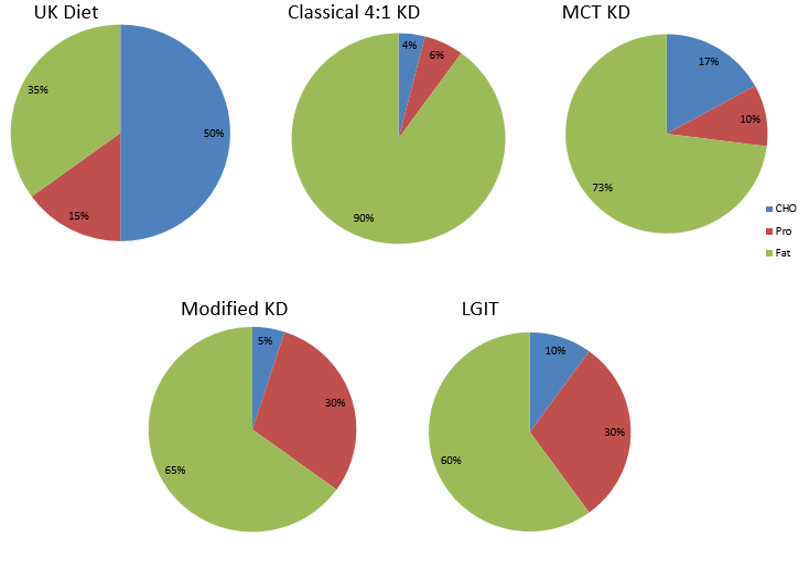

There are several variations of KDT, with differing proportions of fat/carbohydrate/protein and how they are implemented.

The classical ketogenic diet (KD) works on a ratio of grams of fat to grams of protein and carbohydrate – typically, the highest ratio used is 4:1 (4g of fat to every 1g of protein and carbohydrate combined), which provides close to 90% total energy from fat.

In the 1970s, Huttenlocher introduced the Medium Chain Triglyceride (MCT) KD, which originally derived 60% of its calories from MCT oil.1 MCTs are more ketogenic per calorie, and so this type of KD allowed a greater bulk of protein and carbohydrate compared to the predominantly long-chain fat classical KD. A modified MCT KD was later developed, designed to minimise the gastrointestinal side effects of MCT, including 30% total calories from MCT oil and 41% from long-chain fats.2

The Modified Atkins Diet (MAD) was developed in the 2000s from Johns Hopkins Hospital as a more liberal alternative to the classical KD, with fats ‘encouraged’ rather than specifically measured, and protein unlimited to aid compliance and reduce the burden of dietary implementation and education.3 In the UK, a modified ketogenic diet (MKD) is commonly used, which is a hybrid between the classical KD and MAD.4

The Low Glycaemic Index Treatment (LGIT) was introduced in 2005 from Boston.5 This allows up to ~50g of carbohydrates per day, but only including carbohydrates with a glycaemic index of <50.

Fig 1: Approximate macronutrient composition of UK ‘standard’ diet and types of ketogenic diet therapy

What is ketogenic diet therapy used for?

KDT is the treatment of choice for certain neurometabolic conditions, for example glucose transporter type 1 deficiency syndrome. They are also a well-established treatment for children with drug-resistant epilepsy (those who continue to have seizures despite having tried two or more anti-seizure medicines). There are randomised controlled trials showing that children who follow KDT are over three times more likely to achieve seizure freedom, and almost six times more likely to achieve ≥50% seizure reduction at three to four months compared to usual care.6 For some epilepsy conditions, KDT may be particularly beneficial to use early on in the course of the condition. Two randomised controlled trials looked at the MAD for adults with epilepsy, showing adults to be five times more likely to achieve ≥50% seizure reduction compared to usual care.6 No adults achieved seizure freedom. It should be noted that the evidence for adults has been described as of “very low certainty”.

KDT is recommended in NICE guidelines for children with specific childhood-onset epilepsy syndromes, and for people with drug-resistant epilepsy “if other treatment options have been unsuccessful or are not appropriate”.7

There were approximately 800 children on KDT in 2022 (Ketogenic Dietitians Research Network (KDRN) survey), cared for within approximately 30 specialist centres.

In recent years there has been growing interest in use of KDT for conditions other than epilepsy. Pilot or feasibility studies have been published for conditions such as autism spectrum disorder,8 glioblastoma,9 Alzheimer’s disease,10 Parkinson’s disease,11 cluster headaches12 and lung and pancreatic cancer.13 There are also pre-clinical studies for conditions such as gastrointestinal cancers,14-16 classic motor neurone disease17 and traumatic brain injury.18, 19

Randomised controlled trials have been conducted including patients with overweight or obesity, and with and without type 2 diabetes, on a ketogenic diet. A meta-analysis of 14 studies showed that, compared to low-fat diets, KDs led to greater weight reduction, irrespective of patients’ diabetes status at baseline, and lower triglycerides and greater high-density lipoprotein for patients with diabetes.20 KDT lowered glycated haemoglobin for individuals with diabetes to a greater extent than low-fat diets. A very recent meta-analysis of 21 studies of ketogenic diets in patients with obesity or overweight with type 2 diabetes showed similar findings.21 Compared to non-ketogenic diets, KDT exerted a greater impact on lower fasting plasma glucose and glycated haemoglobin, reduced body mass index, weight and waist circumference, lower triglycerides and an upward trend for high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Is ketogenic diet therapy safe?

From studies of individuals with epilepsy, there are a range of side effects that can occur when following KDT, both short and long term, manageable and potentially serious.

Gastrointestinal side effects, such as constipation, diarrhoea or vomiting, occur in up to one-third of individuals in the early stages of KDT. Usually this is transient or managed with medication. Other short-term side effects that are generally easily manageable include lethargy, irritability, respiratory tract infections and exacerbation of reflux. Hypoglyacemia occurs in 1.8% and hyperketosis in 3.1% (from prospective studies).22

Longer-term side effects include renal stones (reported incidence 1.3-3.1%), osteopenia (1.2-14.7%), cardiomyopathy (0.8%), pancreatitis (0.1-0.8%) and bruising (0.3%).22 Adverse effects on lipid profiles have been reported in up to 14.7%, although such effects have been shown to normalise over time and return to baseline after discontinuing KDT.23-25 A prospective study has illustrated the cardiovascular safety of the MAD used over 12 months in adults with epilepsy.26

What do medical ketogenic diets look like?

When following KDT, you need not miss out! Here are some mouth-watering examples tried and tested by our clinical teams.

Almond Keto waffle and cream (photo courtesy of Victoria Whiteley)

Avocado and egg salad with tuna mayo and seeds (photo courtesy of Victoria Whiteley)

Roasted celeriac with café du Paris sauce and tofu (photo courtesy of Victoria Whiteley)

There are a wide range of prescribable products available, including milkshakes, cereal bars, and puddings, which help to make KDT more palatable and expand the diversity of patient’s dietary intake.

UK charities The Daisy Garland and Matthew’s Friends support the use of KDs and they have a wide range of ketogenic recipes available.

Conclusion

KDT is a well-established treatment for epilepsy and certain neurometabolic disorders, but the evidence base for use of KDT for other conditions is ever increasing. This is exciting and ketogenics is a dynamic specialism to work in. However, KDT is not a ‘natural’ treatment option and the diets have well-reported adverse effects. All KDT should be implemented and monitored under the management of an experienced KD team.

References

- Huttenlocher PR, Wilbourn AJ, Signore JM. Medium-chain triglycerides as a therapy for intractable childhood epilepsy. Neurology. 1971;21(11):1097-103.

- Schwartz RM, Boyes S, Aynsley-Green A. Metabolic effects of three ketogenic diets in the treatment of severe epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1989;31(2):152-60.

- Kossoff EH, McGrogan JR, Bluml RM, Pillas DJ, Rubenstein JE, Vining EP. A modified Atkins diet is effective for the treatment of intractable pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47(2):421-4.

- Martin-McGill KJ, Lambert B, Whiteley VJ, Wood S, Neal EG, Simpson ZR, et al. Understanding the core principles of a ‘modified ketogenic diet’: a UK and Ireland perspective. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2019;32(3):385–90.

- Pfeifer HH, Thiele EA. Lowglycemic- index treatment: a liberalized ketogenic diet for treatment of intractable epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1810-2.

- Martin-McGill KJ, Bresnahan R, Levy RG, Cooper PN. Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6:CD001903.

- Excellence. NIfC. Epilepsies in children, young people and adults. NICE guideline [NG217]. 2022.

- Evangeliou A, Vlachonikolis I, Mihailidou H, Spilioti M, Skarpalezou A, Makaronas N, et al. Application of a ketogenic diet in children with autistic behavior: pilot study. J Child Neurol. 2003;18(2):113-8.

- Martin-McGill KJ, Srikandarajah N, Marson AG, Tudur Smith C, Jenkinson MD. The role of ketogenic diets in the therapeutic management of adult and paediatric gliomas: a systematic review. CNS Oncol. 2018;7(2):CNS17.

- Taylor MK, Sullivan DK, Mahnken JD, Burns JM, Swerdlow RH. Feasibility and efficacy data from a ketogenic diet intervention in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:28-36.

- Phillips MCL, Murtagh DKJ, Gilbertson LJ, Asztely FJS, Lynch CDP. Low-fat versus ketogenic diet in Parkinson’s disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2018;33(8):1306-14.

- Di Lorenzo C, Coppola G, Di Lenola D, Evangelista M, Sirianni G, Rossi P, et al. Efficacy of Modified Atkins Ketogenic Diet in Chronic Cluster Headache: An Open-Label, Single-Arm, Clinical Trial. Front Neurol. 2018;9:64.

- Zahra A, Fath MA, Opat E, Mapuskar KA, Bhatia SK, Ma DC, et al. Consuming a Ketogenic Diet while Receiving Radiation and Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Lung Cancer and Pancreatic Cancer: The University of Iowa Experience of Two Phase 1 Clinical Trials. Radiat Res. 2017;187(6):743-54.

- Otto C, Kaemmerer U, Illert B, Muehling B, Pfetzer N, Wittig R, et al. Growth of human gastric cancer cells in nude mice is delayed by a ketogenic diet supplemented with omega-3 fatty acids and mediumchain triglycerides. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:122.

- Hao GW, Chen YS, He DM, Wang HY, Wu GH, Zhang B. Growth of human colon cancer cells in nude mice is delayed by ketogenic diet with or without omega-3 fatty acids and medium-chain triglycerides. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(5):2061-8.

- Tisdale MJ, Brennan RA. A comparison of long-chain triglycerides and medium chain triglycerides on weight loss and tumour size in a cachexia model. Br J Cancer. 1988;58(5):580-3.

- Paganoni S, Wills AM. High-fat and ketogenic diets in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(8):989-92.

- Appelberg KS, Hovda DA, Prins ML. The effects of a ketogenic diet on behavioral outcome after controlled cortical impact injury in the juvenile and adult rat. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(4):497-506.

- White H, Venkatesh B. Clinical review: ketones and brain injury. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):219.

- Choi YJ, Jeon SM, Shin S. Impact of a Ketogenic Diet on Metabolic Parameters in Patients with Obesity or Overweight and with or without Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2020;12(7).

- Luo W, Zhang J, Xu D, Zhou Y, Qu Z, Yang Q, et al. Low carbohydrate ketogenic diets reduce cardiovascular risk factor levels in obese or overweight patients with T2DM: A metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1092031.

- Cai QY, Zhou ZJ, Luo R, Gan J, Li SP, Mu DZ, et al. Safety and tolerability of the ketogenic diet used for the treatment of refractory childhood epilepsy: a systematic review of published prospective studies. World J Pediatr. 2017;13(6):528-36.

- Kapetanakis M, Liuba P, Odermarsky M, Lundgren J, Hallbook T. Effects of ketogenic diet on vascular function. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(4):489-94.

- Liu YM, Lowe H, Zak MM, Kobayashi J, Chan VW, Donner EJ. Can children with hyperlipidemia receive ketogenic diet for medication-resistant epilepsy? J Child Neurol. 2013;28(4):479-83.

- Patel A, Pyzik PL, Turner Z, Rubenstein JE, Kossoff EH. Long-term outcomes of children treated with the ketogenic diet in the past. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1277-82.

- Cervenka MC, Patton K, Eloyan A, Henry B, Kossoff EH. The impact of the modified Atkins diet on lipid profiles in adults with epilepsy. Nutritional neuroscience. 2016;19(3):131-7.