Dietitian Chloe Hall looks at Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS), how it can be treated and how a dietitian can help.

Let me start by asking if you have even heard of MCAS? I certainly hadn’t right at the beginning of my husband’s journey, but the research I’ve done over the years due to his diagnosis has helped me to support many others who either have a diagnosis or have ‘suspected MCAS’.

Unfortunately, as I’ll explain in this article, awareness of this condition, among many health professionals and the general public, is currently lacking and a patient’s journey to gain a diagnosis is - usually - not straightforward. This little-known condition is becoming more well-known however, as there has been a suggestion that COVID may trigger or exacerbate MCAS in some patients1. I am passionate about raising awareness about this condition and about how we as dietitians can help those with MCAS.

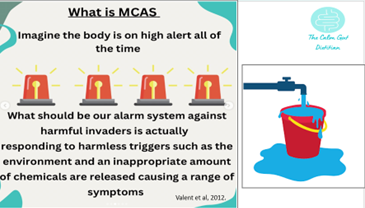

What is MCAS?

A mast cell is a blood cell that plays a key role in our immune system2. These cells produce many mediators including pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines, including histamine, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins3.

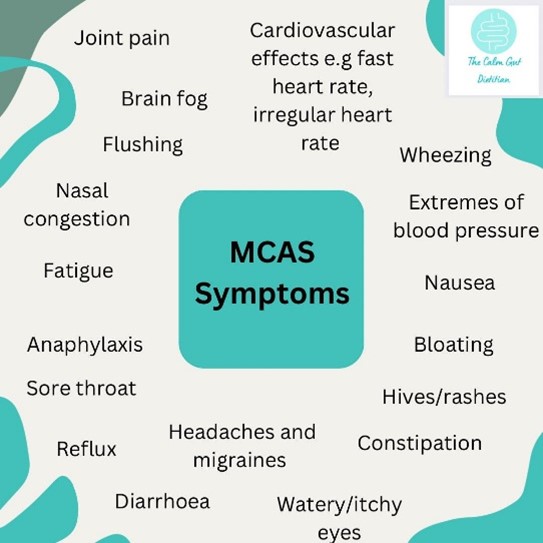

What are the symptoms of MCAS?

There are mast cells located in all vascularized tissues of the body, apart from the central nervous system and the retina, and, therefore, symptoms can affect a range of systems within the whole body2,4.

How is MCAS diagnosed?

Diagnosis is not straightforward due to the complexity of the condition and a lack of awareness by health professionals and often patients can end up seeing multiple consultants for different specialties, such as cardiologists, dermatologists and gastroenterologists, without gaining a diagnosis that describes the holistic condition.

The term MCAS was only introduced in 2007 and the first expert-agreed diagnostic criteria published in 2012, and, therefore, the concept is fairly new to a lot of health professionals4. In addition to this, there is no single specialty within the NHS that diagnoses or manages MCAS and patients often end up with a ‘suspected MCAS’ diagnosis through seeing one of the above specialties or opting for private care. The diagnostic journey can be distressing and frustrating for patients and a lot of patients are frequently told their symptoms are psychosomatic, even though they would meet the diagnostic criteria for MCAS. This lack of awareness can contribute to anxiety and depression and cause those with MCAS to feel even more isolated5.

Four steps are used in the diagnosis of MCAS6,7, 8. These steps involve the following:

- The patient presenting with typical MCAS symptoms across multiple body symptoms.

- Biochemical evidence of mediator release from mast cells. Serum tryptase is the most commonly used and should be collected within 4 hours following an MCAS symptom episodes and compared to levels collected 24–48 hours later. If tryptase is negative it doesn’t, however, exclude MCAS, but a positive test can contribute to the evidence for a diagnosis of MCAS6.

- Using an MCAS treatment and seeing if there is any response; an ‘empirical’ trial.

- Ruling out other causes of symptoms such as irritable bowel syndrome, autoimmune disorders, neoplasms, infectious diseases, adrenal insufficiency and cardiovascular disorders6.

What other conditions are linked to MCAS?

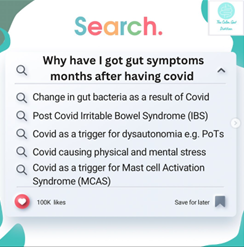

There are many co-morbidities that are thought to be associated with MCAS and in practice I often see co-existing diagnoses of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia (PoTS), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and most recently Long Covid9,10.

Could post-Covid/Long Covid symptoms be linked to MCAS?

Many post-Covid symptoms are the same as MCAS, and, therefore, it has been proposed that Covid may trigger or exacerbate MCAS in some people1,11. It has been suggested that the hyper-inflammatory responses seen in acute covid infections, and in Long Covid, may be mediated in part by mast cell activation12,13. In view of this, H1 and H2 antihistamines, which are often used in MCAS treatment, are already being used to treat those with Long Covid and other treatments such as mast cell stabilisers are being tested in clinical trials for this purpose14,1. Covid, also, appears to trigger PoTS in some people and there is a known overlap between MCAS and PoTs15. It's really important, however, that not all Long Covid symptoms or presentations are attributed to MCAS, as there may be other causes1.

There have, also, been anecdotal reports that the low histamine diet, a diet often used to control symptoms in MCAS, may be helpful for some people with Long Covid. Due to a lack of clinical trials for its use with Long Covid symptoms, this is not something currently recommended as a first-line treatment. However, if histamine intolerance is suspected on an individual basis then it is vital that a dietitian supports those who want to try the diet, as it can be nutritionally and socially restrictive.

What are the common triggers of MCAS?

MCAS triggers are very individual and can vary widely, however common triggers include:

- Insect or snake bites1

- Pollen season3

- Stress3,16

- Certain medications1,3

- Infections 1,17

- Caffeine18

- Alcohol19, 1

- Dietary triggers1,20,9

- Chemicals1, 20, 9

- Fragrances1, 20, 9

- Extreme temperatures7

- Physical stimulation e.g. pressure or friction1

Often the ‘histamine bucket’ theory is used when discussing triggers with patients i.e. different triggers may cause the histamine bucket to fill up and if your body isn’t breaking the histamine down quickly enough to empty that bucket, then the bucket may overflow and cause symptoms.

It is important to remember, however, that histamine is only one of the many mediators produced by the mast cells so controlling histamine levels is only one aspect of controlling the symptoms of MCAS4.

What dietary issues may those with MCAS present with?

There are no large-scale, high-quality clinical trials to date that look at the dietary intake of those with MCAS. In practice, we see a wide range of dietary issues associated with MCAS, including low body weight, weight loss and nutrient deficiencies. These often occur through restricted diets as a result of confirmed dietary trigger removal, elimination diets to try and determine triggers, or because the patient’s symptoms are so debilitating that cooking, shopping and eating become a huge challenge.

A recent survey by Mast Cell Action, a UK charity that supports those with MCAS, of 142 patients showed that the majority of these patients were using a dietary strategy to try and control their symptoms21. Some of the strategies used by those in this survey included the low histamine diet, dairy-free, gluten-free, low salicylates, low oxalate or the low FODMAP diet. Dietetic support for these patients is essential, to ensure that the diet is balanced and nutritionally adequate and that these dietary restrictions don’t cause further problems.

Unfortunately, in many areas dietetic support for these patients on the NHS is difficult to access, not available or patients have been put off seeking help due to the lack of awareness of the condition.

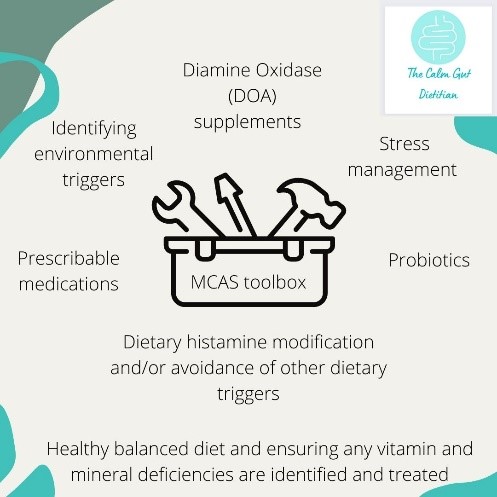

The treatment of MCAS

There is no cure for MCAS at present. However medications can be used to reduce symptoms by reducing the production or action of mast cell mediators and/or stabilising mast cells1,22. These include, but are not limited to, H1 and H2 antihistamines such as fexofenadine and famotidine, mast cell stabilisers such as ketotifen and anti-leukotrienes such as Montelukast. Treatment also involves avoiding any known personal triggers for MCAS. However, this can be extremely challenging as some of these may be environmental and hard to control e.g. other people wearing perfume, cleaning products and pollen22.

The low histamine diet and MCAS

There is no official diet recommended for MCAS, however, many patients with MCAS find that dietary histamine modification helps to control some of the many symptoms associated with MCAS21. A global consensus of health professionals concluded that histamine contributed substantially to the clinical symptoms of MCAS with a consensus level of 95%, and as ingested histamine ‘tops up the bucket’, reducing dietary histamine may be helpful4.

The low histamine diet should be a short-term elimination diet followed for two to four weeks followed by a systematic re-introduction of foods to identify individual triggers for symptoms. Dietetic support whilst following the low histamine diet is really important as the diet can be restrictive. Ongoing dietetic support for the low histamine diet and those with MCAS can, also, be helpful as dietary triggers can change and often people with MCAS have ‘flare ups’ and then periods where their symptoms are more stable and they can eat a wider range of foods1.

As discussed earlier in this article, the histamine bucket theory may explain why those with MCAS and/or histamine intolerance may be able to eat more histamine-rich foods during times of lower external triggers such as relaxation periods or outside of pollen season.

There is, however, no definitive consensus as to the histamine content of foods and many different lists can be found, which can be confusing for patients and result in a more restrictive diet than necessary. Histamine content of foods, even ones generally accepted as low histamine, can vary widely depending on factors such as storage conditions and how fresh they are23.

Some lists suggest restricting ‘histamine-releasing foods’, however there is little evidence to suggest that these foods cause mast cells to release histamine in the body24. In practice, advice regarding food storage can be helpful to reduce overall dietary histamine. As freezing can slow histamine production, I often suggest freezing leftovers instead of leaving them in the fridge and freezing meat on the day of purchase and defrosting before use.

Other dietary factors and MCAS

Some gut microbiota have the potential to produce histamine and others may help to break it down25,26,27. Many patients with MCAS experience gut symptoms21 and, therefore, some patients try probiotics to try and reduce these symptoms. It is important to choose probiotics that contain the bacterial strains thought to be helpful in breaking down histamine and avoid those that produce histamine and, therefore, we as dietitians can help guide patients in choosing the right probiotic.

Some micronutrients are thought to contribute to mast cell stabilization such as Vitamin C and D1. It has, also, been suggested that Vitamin C contributes to histamine breakdown7. As some common foods high in Vitamin C are restricted on most low histamine diets, such as tomatoes and citrus fruits, dietitians can play an essential role in helping those with MCAS find sources of vitamin C that they can tolerate.

What can we do to help those with MCAS as dietitians?

MCAS can have a significant negative impact on a patient’s quality of life. However even slight improvements in a patient's level of information can help to improve this28. As dietitians we can help to communicate evidence-based information on diet and MCAS to patients and help improve their understanding.

As previously detailed, dietary triggers can play a significant role in symptoms and, therefore, dietitians can help those with MCAS identify their own personal dietary triggers and exclude them in a safe way without compromising their nutritional intake and social enjoyment. Often patients present having already undertaken their own elimination diets and are understandably fearful of re-introducing foods due to the extreme reactions they have had in the past, which can include anaphylaxis. Dietitians can help to support patients in safely re-introducing foods.

Much of my role as a Dietitian specialising in MCAS, histamine intolerance and gut health focuses on helping these patients enjoy food again, as often MCAS patients feel left out of celebrations that involve food such as Christmas, birthdays and meals out. The more awareness there is of the condition and of what can help, the bigger role we can play in helping those with MCAS achieve a healthy and happy life despite a very difficult chronic condition.

References

- Arun S, Storan A, Myers B. Mast cell activation syndrome and the link with long COVID. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2022 Jul 2;83(7):1-10. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2022.0123. Epub 2022 Jul 26

- da Silva EZ, Jamur MC, Oliver C. Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014 Oct;62(10):698-738. doi: 10.1369/0022155414545334. Epub 2014 Jul 25.

- Giannetti, A.; Filice, E.; Caffarelli, C.; Ricci, G.; Pession, A. Mast Cell Activation Disorders. Medicina 2021, 57, 124. https://doi. org/10.3390/medicina57020124

- Valent P, Akin C, Arock M, Brockow K, Butterfield JH, Carter MC, Castells M, Escribano L, Hartmann K, Lieberman P, Nedoszytko B, Orfao A, Schwartz LB, Sotlar K, Sperr WR, Triggiani M, Valenta R, Horny HP, Metcalfe DD. Definitions, criteria and global classification of mast cell disorders with special reference to mast cell activation syndromes: a consensus proposal. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157(3):215-25. doi: 10.1159/000328760. Epub 2011 Oct 27.

- Jennings SV, Slee VM, Hempstead JB, et al. The Mastocytosis Society (TMS) Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS) Patient Perceptions Survey. AAAAI Annual Meeting 2018. Available at: https://tmsforacure.org/wp-content/uploads/MCAS.Survey.Poster_The.Mastocytosis.Society.Inc_for.AAAAI_.2019_042219_web.p

- Weiler CR. Mast Cell Activation Syndrome: Tools for Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(2):498–506;

- Molderings GJ, Brettner S, Homann J, Afrin LB. Mast Cell Activation Disease: A Concise Practical Guide for Diagnostic Workup and Therapeutic Options. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:10;

- Valent P, Akin C, Bonadonna P, et al. Proposed Diagnostic Algorithm for Patients with Suspected Mast Cell Activation Syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(4):1125-1133.e1;

- Theoharides TC, Tsilioni I, Ren H. Recent advances in our understanding of mast cell activation - or should it be mast cell mediator disorders?. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(6):639-656. doi:10.1080/1744666X.2019.1596800

- Afrin LB, Weinstock LB, Molderings GJ. Covid-19 hyperinflammation and post-Covid-19 illness may be rooted in mast cell activation syndrome. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Nov;100:327-332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.016. Epub 2020 Sep 10.

- Weinstock LB, Brook JB, Walters AS et al. Mast cell activation symptoms are prevalent in long- COVID. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;112:217–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.043

- Kritas, S. K., G. Ronconi, A. Caraffa, C. E. Gallenga, R. Ross and P. Conti (2020). "Mast cells contribute to coronavirus-induced inflammation: new anti-inflammatory strategy." J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 34(1): 9-14.

- Theoharides, T. C. (2021). "Potential association of mast cells with coronavirus disease 2019." Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 126(3): 217-218.

- Davis H, Assaf G, McCorkell L et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. E Clin Med. 2021;38(101019):101019–101013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. eclinm.2021.101019

- Dixit NM, Churchill A, Nsair A, Hsu JJ. Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome and the cardiovascular system: What is known? Am Heart J Plus. 2021 May;5:100025. doi: 10.1016/j.ahjo.2021.100025. Epub 2021 Jun 24. PMID: 34192289; PMCID: PMC8223036.

- Eutamene, H., V. Theodorou, J. Fioramonti and L. Bueno (2003). "Acute stress modulates the histamine content of mast cells in the gastrointestinal tract through interleukin-1 and corticotropin-releasing factor release in rats." J Physiol 553(Pt 3): 959-966.

- Afrin LB, Ackerley MB, Bluestein LS, Brewer JH, Brook JB, Buchanan AD, Cuni JR, Davey WP, Dempsey TT, Dorff SR, Dubravec MS, Guggenheim AG, Hindman KJ, Hoffman B, Kaufman DL, Kratzer SJ, Lee TM, Marantz MS, Maxwell AJ, McCann KK, McKee DL, Menk Otto L, Pace LA, Perkins DD, Radovsky L, Raleigh MS, Rapaport SA, Reinhold EJ, Renneker ML, Robinson WA, Roland AM, Rosenbloom ES, Rowe PC, Ruhoy IS, Saperstein DS, Schlosser DA, Schofield JR, Settle JE, Weinstock LB, Wengenroth M, Westaway M, Xi SC, Molderings GJ. Diagnosis of mast cell activation syndrome: a global "consensus-2". Diagnosis (Berl). 2020 Apr 22;8(2):137-152.

- John, J., T. Kodama and J. M. Siegel (2014). "Caffeine promotes glutamate and histamine release in the posterior hypothalamus." Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 307(6): R704-710.

- Wantke, F., M. Götz and R. Jarisch (1994). "The red wine provocation test: intolerance to histamine as a model for food intolerance." Allergy Proc 15(1): 27-32.

- Akin C. Mast cell activation syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(2):349–355. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.06.007

- Dear Doctor, Could your patient’s unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms be caused by Mast Cell Activation Syndrome? Ruth Slater and Helen Bowes Mast Cell Action, UK 2021. Accessed mca-bsg-campus-2020-poster-final.pdf (mastcellaction.org)

- Molderings GJ, Haenisch B, Brettner S, Homann J, Menzen M, Dumoulin FL, Panse J, Butterfield J, Afrin LB. Pharmacological treatment options for mast cell activation disease. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2016 Jul;389(7):671-94. doi: 10.1007/s00210-016-1247-1. Epub 2016 Apr 30.

- Skypala IJ, Williams M, Reeves L, Meyer R, Venter C. Sensitivity to food additives, vaso-active amines and salicylates: a review of the evidence. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015 Oct 13;5:34. doi: 10.1186/s13601-015-0078-3. PMID: 26468368; PMCID: PMC4604636.

- Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, van der Heide S, Oude Elberink JN, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Dubois AE. Mastocytosis and adverse reactions to biogenic amines and histamine-releasing foods: what is the evidence? Neth J Med. 2005;63:244–9

- Pugin B, Barcik W, Westermann P, Heider A, Wawrzyniak M, Hellings P, Akdis CA, O'Mahony L. A wide diversity of bacteria from the human gut produces and degrades biogenic amines. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2017 Jan 1;28(1):1353881. doi: 10.1080/16512235.2017.1353881. PMID: 28959180; PMCID: PMC5614385.

- Barcik W, Pugin B, Brescó MS, Westermann P, Rinaldi A, Groeger D, Van Elst D, Sokolowska M, Krawczyk K, Frei R, Ferstl R, Wawrzyniak M, Altunbulakli C, Akdis CA, O'Mahony L. Bacterial secretion of histamine within the gut influences immune responses within the lung. Allergy. 2019 May;74(5):899-909. doi: 10.1111/all.13709. Epub 2019 Feb 7. PMID: 30589936.

- Schnedl WJ, Enko D. Histamine Intolerance Originates in the Gut. Nutrients. 2021 Apr 12;13(4):1262. doi: 10.3390/nu13041262. PMID: 33921522; PMCID: PMC8069563.

- Schmidt TJ, Sellin J, Molderings GJ, Conrad R, Mücke M. Health-related quality of life and health literacy in patients with systemic mastocytosis and mast cell activation syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022 Jul 29;17(1):295. doi: 10.1186/s13023-022-02439-x. PMID: 35906626; PMCID: PMC9336039.