What, and how, children eat can affect their mood, behaviour and learning. The best diet for good mood, behaviour and learning is one that includes a regular eating pattern and a variety of food.

Eating a varied diet

We need many different nutrients in our diet to support our brain. These include vitamins, essential fats and amino acids (found in protein). The best way to get them is by eating a varied diet.

A large, well-designed study of adolescents showed that “healthier” dietary patterns contributed to better mood, and “unhealthy” dietary patterns led to poor mood. The same study was able to show that poor mood did not cause an unhealthy dietary pattern.

Eating regular meals

Eating regular meals helps to regulate blood sugar. This may influence some of the hormones that control our mood and ability to concentrate. For this reason, poor mood and behaviour are often observed in children who have been without food for too long (for example, children who haven’t eaten breakfast).

The importance of specific nutrients for the brain

Some nutrients seem to be particularly important for the brain. These include minerals like iron, zinc, magnesium and iodine; vitamin D; B vitamins and omega-3 fatty acids. In addition, dietary fibre from plant-based foods may also be important.

Studies of Single Nutrients

Studies using individual nutrients to improve mood, behaviour or learning in children often produce disappointing results. This is probably because nutrients work together rather than alone.

Vitamin D and omega-3

There is some evidence that vitamin D and omega-3 supplements can help with mood or attention in some vulnerable children. This is not surprising because both children and adults in the UK often have low levels of these nutrients.

Omega-3 supplements may improve attention in ADHD and irritability in autism. There is some evidence that omega-3 can improve mood and reduce anxiety in people with those difficulties, but this evidence is mostly from studies with adults.

Vitamin D may help reduce irritability and hyperactivity in autistic children. It may also improve inattention in children with ADHD, especially if they are deficient.

The best ways to get enough of vitamin D is to expose the skin to sunlight in the summer months (without burning). Most children would benefit from a vitamin D supplement.

Dietary sources of important nutrients for the brain

Oily fish is a good source of omega-3. Current dietary advice on fish is to include two portions each week, including at least one portion of oily fish (such as sardines, herring, mackerel or salmon). Seafood is rich in other nutrients too. For children who do not eat fish, omega-3 can be found in walnuts, flaxseeds, chia seeds, leafy green vegetables and rapeseed oil.

Red meat is a good source of iron and zinc, however too much red meat is not recommended. Instead sources of iron and zinc can also be found in pulses, nuts, beans, green vegetables, bread and breakfast cereals.

Green vegetables are a good source of magnesium.

Fish, milk, yoghurt and eggs are a good source of iodine.

“Multi-nutrient” supplements

In theory, any child who is struggling to eat a varied diet, could benefit from a multi-nutrient supplement giving a wide range of vitamins and minerals. There is some evidence that children with ADHD, in particular, might benefit from this kind of supplement.

The importance of dietary fibre for mood and learning

It is well known that fibre is important for gut health. It also seems to help regulate blood sugar, which may help with mood and attention.

The positive effects on mood and attention of eating a meal, may last for a shorter time if there is less fibre. This may be why children have been shown to perform better in tests of attention and memory, two hours after a high fibre breakfast cereal, when compared to a high sugar, low fibre one.

Dietary fibre and some fermented foods (like live yoghurt) may also promote a healthy “microbiome” (the name given to the billions of micro-organisms living in our gut). This may, in turn, also contribute to good mood and general wellbeing, in ways that are not yet fully understood.

Dietary sources of fibre

Most plant-based foods contain dietary fibre. Examples include, fruits, vegetables, wholegrain cereals, beans, nuts and pulses. However, sometimes the fibre is removed or reduced during food processing (for example in white bread, fruit juice and some breakfast cereals).

What does an adequate and varied diet look like?

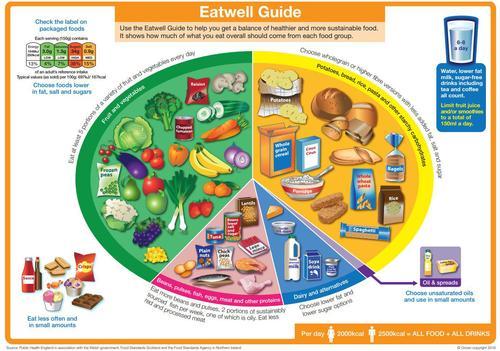

For most children over two years of age (and adults), if they are including a variety of foods from each of the food groups of the Eatwell Guide on a daily basis, they are likely to be getting most of what they need.

Food intolerance

Some children have food intolerance(s) which can mean that their mood or behaviour are affected by specific foods or ingredients. These can produce physical symptoms too.

If you believe your child may have a food intolerance, you should discuss your concerns with your GP or dietitian. They may recommend an “exclusion diet” – where the food is completely removed from your child’s diet and later re-introduced it to see if there is a consistent impact on mood or behaviour.

Top tips

- Eating a wide variety of nutritious foods helps mood, attention and learning.

- Eating regular meals also helps promote good mood and attention.

- Including foods that are rich in dietary fibre may also help.

- Nutritional supplements may help some children. This is especially true when the diet is low in any particular nutrients.

A dietitian is uniquely qualified to provide an accurate assessment of the diet and any risk of deficiency. They can also provide practical advice on the best way to improve nutrition through changes to the diet, nutritional supplements or both.

Source(s)

Adams et al. (1996) Arachidonic acid to eicosapentaenoic acid ratio in blood correlates positively with clinical symptoms of depression. Lipids 31 157-161.

Amminger G.P et al (2007) Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in children with autism: a double-blind randomized, placebo controlled pilot study. Biological Psychiatry 61 (4): 551-3.

Arnold E; Bozollo H; Hollway J (2005) Serum Zinc Correlates with Parent- and Teacher-Rated Inattention in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology 15, 4, 628-636.

Barragán, Breuer, and Döpfner, 2014, Efficacy and Safety of Omega-3/6 Fatty Acids, Methylphenidate, and a Combined Treatment in Children With ADHD

Bell G; MacKinlay E; Dick J et. al (2004) Essential fatty acids and phospholipase A2 in autistic spectrum disorders. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 71 201-204.

Bilici M; Yıldırım F; Kandil S et. al (2004) Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of zinc sulfate in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 28, 181– 190.

Bloch, Qawasmi, 2011, Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation for the Treatment of Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptomatology: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Burgess JR, Stevens L, Zhang W, Peck L. 2000. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71(suppl):327S–330S.

Coppen A, Bolander-Gouaille C (2005) Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12. Journal of Psychopharmacology 19 (1) pp 59-65.

Dienke, Oranje1, Veerhoek1, Van Diepen1, Weusten1, Demmelmair2, Koletzko, 2015, Reduced Symptoms of Inattention after Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation in Boys with and without Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Food Standards Agency (2013) Food colours and hyperactivity [online] available from < http://www.food.gov.uk/policy-advice/additivesbranch/foodcolours/#.USzDTR2-2Sp> [last accessed 26/02/13]

Freeman M P et al (2006) Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Evidence Basis for Treatment and Future Research in Psychiatry. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67: 1954-1966.

Gillie O (2008) Scotland’s Health Deficit – An explanation and a plan. Health Research Forum Occasional Reports: No 3. Health Research Forum. London.

Hibbeln J; Davis J; Steer C et. al (2007) Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): an observational cohort study. Lancet 369 (9561): 578-85.

HMSO (2004) Advice on fish consumption: benefits and risks. Joint report by SACN and COT. TSO, London.

Johnson M et al (2009) Omega-3/Omega-6 Fatty Acids for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial in Children and adolescents. Journal of Attention Disorders. Vol 12 No. 5 pp 394-401.

Kesby J P et al (2011)The effects of vitamin D on brain development and adult brain function. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. Article in press – Available on line June 1st 2011.

MacDonell L; Skinner F; Ward et. al (2000) Increased levels of phospholipase A2 in dyslexics. Prostoglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 63 37-39.

Mahoney,Taylor, Kanarek, Samuel, 2005, Effect of breakfast composition on cognitive processes in elementary school children

Mocking, Harmsen1, Assies1, Koeter1, Ruhé, and Schene, 2016, Meta-analysis and meta-regression of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for major depressive disorder

Montgomery, Burton, Sewell, Sprecklesen and Richardson, 2014, Fatty acids and sleep in UK children: subjective and pilot objective sleep results from the DOLAB study – a randomizedcontrolled trial

National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2010). Headline results from year 1 of the rolling programme 2008/2009 Eds: Bates, B; Lennox, A; Swan G.

Otero G; Pliego-Rivero F; Contreras G et. Al (2004) Iron Supplementation Brings up a Lacking P300 in Iron Deficient Children. Clinical Neurophysiology 115, 2259–2266.

Peet M et. al (1998) Depletion of omega 3 fatty acid levels in red blood cell membranes of depressive patients. Journal of Biological Psychiatry 43 315-319.

Pelsser L; Frankena K; Toorman J et. al (2011) Effects of a restricted elimination diet on the behaviour of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (INCA study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 377: 494–503.

Practice-based Evidence in Nutrition (2011) Is there any evidence to support essential fatty acid (EFA) supplementation for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)? [online] available by subscription from < http://www.pennutrition.com/KnowledgePathway.aspx?kpid=4544&pqcatid=146&pqid=4508> [last accessed 21/02/13]

Richardson A J, Montgomery P (2005) RCT of fatty acid supplementation in children with DCD. Pediatrics. 115 (5): 1360-1366.

Schab D W (2004) Do artificial food colours promote hyeractivity in children with hyperactive syndromes? A meta-analysis of double blind placebo controlled trials Journal of developmental and behavioural paediatrics. - 6 : Vol. 25. - pp. 423-434.

Scientific Advisory Committeeon Nutrition (2011) The Influence of maternal, fetal and child nutrition on the development of chronic disease in later life [online] available from < http://www.sacn.gov.uk/pdfs/sacn_early_nutrition_final_report_20_6_11.pdf> [last accessed 25/02/13]

Sinn N, Bryan J (2007) Effect of supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids and micronutrients on learning and behaviour problems associated with child ADHD. Journal of Developmental & Behavioural Behavioural Pediatrics. 28 82-91.

Starobrat-Hermelin B; Kozielec (1997) The effects of magnesium physiological supplementation on hyperactivity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Positive response to magnesium oral loading test. Magnesium research. 10 (2), 149-56.

Stevenson J (2007) Food additives and hyperactive behaviour in 3 year old and 8/9 year old children in the community: a randomised, double- blinded placebo controlled trial. The Lancet. Vol. 370 No. 9598 pp 1560-1567.

Whiteley P et. al (2010) The ScanBrit randomised, controlled, singleblind study of a gluten- and casein-free dietary intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Nutritional Neuroscience Vol 13, No. 2 , pp 87-100.