Cristian Costas Batlle looks at the challenges of getting accurate diagnosis figures for this growing condition.

Coeliac disease (CD) is an immune mediated multisystem disorder characterised by the presence of damage to the small intestine after the ingestion of gluten in genetically susceptible persons.1 Currently, there is no cure for this disease and the only proven treatment available is a strict and permanent gluten-free diet which involves avoidance of predominantly wheat, barley and rye. As small an amount as 1/100th of a slice of bread (10-50mg of gluten) can cause gut damage and symptoms for those who have CD.2

It is often thought that coeliac disease is a Western or European disease, possibly due to Western diets being more reliant on wheat consumption. However, research clearly shows that coeliac disease affects people across the world.

Although there is not data available for every country in the world, for the countries where data has been collected in Asia, Europe, Africa, South America, North America, and Oceania the prevalence of CD based on serologic test results is 1.4% and based on biopsy results is 0.7%.3 In the UK, the prevalence of CD is estimated to be 1%. However, these are by no means static numbers, as CD prevalence has been shown to be on the increase across the world.4 The increase in prevalence rates makes it even more challenging to ensure enough people get diagnosed. In the UK for example, currently around 75% of people (500,000) remain undiagnosed without knowing it.

Why do half a million people in the UK remain undiagnosed?

Unfortunately this remains a significant challenge for many countries and there are many plausible reasons for this. In recent years there has been an increase in the availability of gluten-free foods which, coupled with speculation about gluten having a negative impact on health, has led to more people following a gluten free diet without having CD.5 Since tests for coeliac disease are only accurate when one is on a gluten-containing diet, many people who decide to venture on a gluten-free diet without getting tested for a medical diagnosis of CD could have coeliac disease without knowing it.

Furthermore, having to follow current Coeliac UK recommendations that advise to eat gluten in at least one meal per day for six weeks prior to diagnosis tests can generate significant symptoms for people and some may stop eating gluten for symptom relief and consequently never get tested properly. The testing process can also be long and challenging for people, as they may have to eat gluten for an extended period of time by first having to eat it to have an antibody blood test and then have to eat it again for an endoscopy test (where duodenal biopsies are taken).

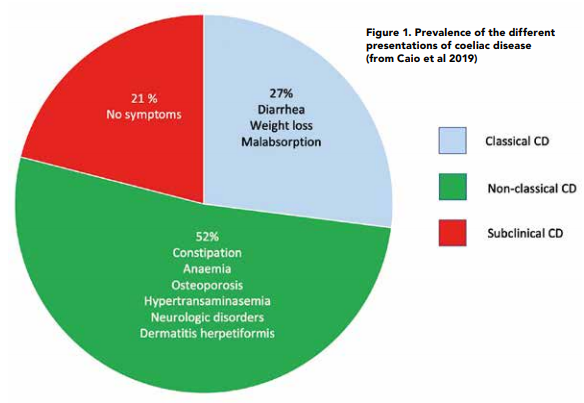

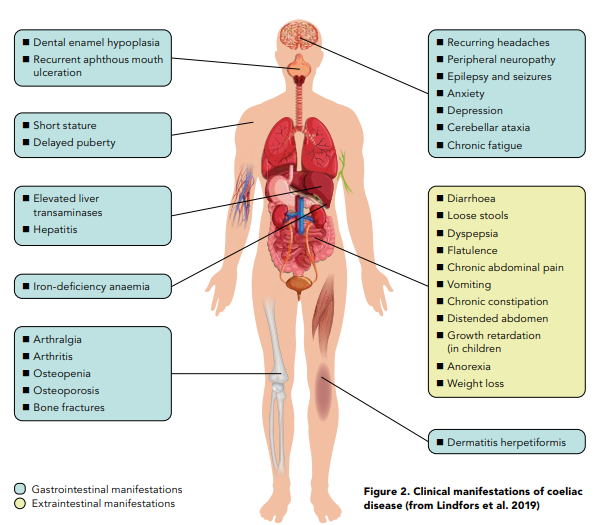

Since CD is a digestive condition that doesn’t just manifest through gut symptoms, this makes things challenging for both health professionals and patients with regards to screening for it. In recent years there has been growing evidence to show that patients are actually more likely to present with the non-classical symptoms of CD6 as per Figure 1. Some of these nonclassical symptoms can be dermatitis herpetiformis (mainly presenting as skin rashes), peripheral neuropathy, mouth ulcers, headaches, fatigue, vitamin and mineral deficiencies and infertility amongst many others. Figure 2 provides an overview of what parts of the body coeliac disease symptoms can manifest in.7 In addition, around 20% of patients can also be asymptomatic. Therefore, it makes sense to have a low threshold for screening for coeliac disease.

For patients who do only have the classical symptoms of coeliac disease (that mainly include abdominal pain, diarrhoea and bloating) diagnosis is not straightforward either. This is because the digestive symptoms of CD are common to other medical conditions, which can lead to patients getting misdiagnosed with another medical condition. Previous data suggests that up to 28% of people with coeliac disease have been misdiagnosed with IBS before receiving a CD diagnosis.8 This is why coeliac disease should always be one of the things to be ruled out before making an IBS diagnosis.

Another common misconception about CD is that it is thought to be a genetic condition with an onset within the early years of life. However, CD can onset at any point through the lifespan and in fact more than 50% of people are diagnosed above the age of 40 in the UK. A lack of awareness about this condition and its symptoms from health professionals and the lay population probably helps to explain why it is underdiagnosed and why it takes 13 years on average to get a diagnosis of coeliac disease in the UK.

How has diagnosis criteria for adults changed recently in the UK?

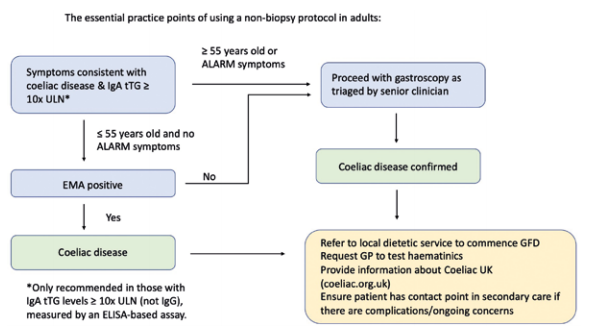

Historically, an antibody blood test and an endoscopy with a duodenal biopsy has always been necessary to diagnose adults with CD in the UK.9 However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic a very large number of endoscopies have not been performed and many hospitals have ended up with large endoscopy waiting lists which can significantly delay the diagnosis of CD. A proposed solution for patients with CD by the British Society of Gastroenterology has been to publish interim guidance suggesting a non-biopsy approach in select patients. This approach takes into account the increasing body of research showing that coeliac antibody blood tests have very high specificity and sensitivity.1 The idea is that if these blood tests show certain values, an endoscopy and duodenal biopsy can be avoided in most patients aged under 55 years as per Figure 3.

This new non-biopsy approach points out that patients can now be diagnosed in primary care by their GP if they do not need an endoscopy. This will hopefully make the diagnosis a lot easier and quicker for many patients who will not need to eat gluten twice to get tested as they may not need an endoscopy; a procedure which patients can find invasive to the point that some will decline it even if it can be diagnostic. The diagram (Figure 3) also highlights the importance of referring patients to a dietitian once diagnosed and therefore it is important that as dietitians we engage with GPs to ensure that this is done and show them all the different ways dietitians can help when it comes to CD. Trott, Costas and Jeanes have highlighted how dietitians can help in CD in a recent article to make GPs aware of this diagnosis change and help ensure all patients get referred to a dietitian.11

Significant challenges remain ahead of us when it comes to diagnosing patients with coeliac disease promptly. The digestive and non-digestive manifestations of coeliac disease coupled with the increasing prevalence of this condition worldwide make it evident to see that we need to be thorough and open minded when we speak to patients to ensure we are not contributing to missing a coeliac disease diagnosis.

However the new non-biopsy approach for select patients should improve true diagnosis rates by making the diagnosis process easier and quicker for patients and clinicians. Furthermore, as dietitians we can further improve the diagnostic process by using our skills to guide patients who we think may need further testing for CD. The more awareness we can raise, the more we can encourage the people who need it to come forward and get tested.

As dietitians, how can we help more people with undiagnosed coeliac disease get the right diagnosis?

We cannot underestimate how much we can help these patients both before and after their diagnosis. Some of the things we can support them with are:

- Coeliac disease has a strong genetic component and first degree relatives have a 10% chance of developing coeliac disease. We can suggest screening for these relatives when symptomatic or asymptomatic, as other health professionals may not always discuss this with the patient.

- If patients want to get tested for CD or we think they should get tested we can signpost patients to fill in a questionnaire on Coeliac UK that will clarify if they should get tested for coeliac disease and they can then take the result to their GP to ensure they get tested.

- We can raise suspicion of coeliac disease if patients have had recurrent unexplained anaemia for years, if they have possible CD suspected symptoms and/or have other autoimmune conditions like autoimmune thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune hepatitis and others.

- When checking if somebody has been tested for coeliac disease we can check how accurate the test has been. It is important to check if the patient has had a Total IgA blood test as well as an IgA-TTG blood test (as if the patient is IgA deficient, the result could give a false negative). We should also check to make sure that the patient was eating gluten consistently for six weeks before the blood test or the endoscopy.

- We must also check that a coeliac screen has actually been done (in the right way as the previous point suggests) in certain cases before giving IBS advice or before giving any advice where it would make sense to check that a coeliac screen has been done first.

References

- Oxentenko A, Rubio-Tapia A. Celiac Disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2019;94(12):2556- 2571.

- Catassi C, Fabiani E, Iacono G, D’Agate C, Francavilla R, Biagi F et al. A prospective, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial to establish a safe gluten threshold for patients with celiac disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;85(1):160-166.

- Singh P, Arora A, Strand T, Leffler D, Catassi C, Green P et al. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2018;16(6):823- 836.e2.

- King J, Jeong J, Underwood F, Quan J, Panaccione N, Windsor J et al. Incidence of Celiac Disease Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2020;115(4):507- 525.

- Kim H, Patel K, Orosz E, Kothari N, Demyen M, Pyrsopoulos N et al. Time Trends in the Prevalence of Celiac Disease and GlutenFree Diet in the US Population. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(11):1716.

- Caio, G., Volta, U., Sapone, A., Leffler, D. A., De Giorgio, R., Catassi, C., & Fasano, A. (2019). Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC medicine, 17(1), 142.

- Lindfors K, Ciacci C, Kurppa K, Lundin K, Makharia G, Mearin M et al. Coeliac disease. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019;5(1).

- Card T, Siffledeen J, West J, Fleming K. An excess of prior irritable bowel syndrome diagnoses or treatments in Celiac disease: evidence of diagnostic delay. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;48(7):801- 807.

- Ludvigsson J, Bai J, Biagi F, Card T, Ciacci C, Ciclitira P et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2014;63(8):1210-1228.