In this chapter:

- The importance of nutrition and allergen information

- Product specifications

- Nutritional analysis

- Recipe analysis

- Recipe types

- Recipe analysis software

- Food labelling legislation

There are two schools of thought about food tables. One tends to regard the figures in them as having the accuracy of atomic weight determinations; the other dismisses them as valueless on the ground that a foodstuff may be so modified by the soil, the season or its rate of growth that no figure can be a reliable guide to its composition. The truth, of course, lies somewhere between these two points of view.

Widdowson and McCance, 1943

Nutrition and allergen information must be readily available for all items on a healthcare menu, regardless of whether they are bought in or prepared onsite. A nutrition analysis of all food and drink items on a menu is the crucial first step in analysing the capacity of a menu (covered in Chapter 11) to ensure it can meet the nutritional needs of patients (as outlined in Chapter 10).

This chapter explores the different methods used to complete a nutritional analysis, what a food supplier is expected to provide in their product specifications and other food labelling requirements.

The importance of nutrition and allergen information

The nutrition and allergen content of food and drink must be known so menus developed in healthcare settings can:

- Meet legislative requirements

- Legislation about what and how food allergens are communicated including, Natasha’s Law and the mandatory declaration of the 14 food allergens

- Calorie Labelling regulations and the nutrition standards of the Government Buying Standards (see Chapter 5)

- Meet the Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Reference Nutrient Intakes (RNIs) for different patient groups

- Be analysed for their capacity to meet the needs of both nutritionally well and nutritionally vulnerable (see Chapter 11) to show compliance with the National standards for healthcare food and drink (1)

- Be coded in line with the menu coding nutrition criteria outlined in this document (see Chapter 12)

- Cater to several different therapeutic, religious, cultural and lifestyle requirements

- Meet contractual requirements.

Product specifications

Manufacturers and suppliers are legally required to provide certain information in their product specifications in line with the food information regulations (2). This includes:

- Name of the food

- List of ingredients, with quantities

- Net quantity of the food

- Minimum durability or the ‘use by’ date

- Storage conditions and/or conditions of use

- Name of business and address

- Country of origin/place of provenance (where necessary)

- Instructions for use

- Nutrition declaration – the minimum mandatory requirement is to provide energy and six nutrients in line with food labelling regulations. The values must be given in the units (including both kJ and kcal for energy) per 100g/ml

The product specification information will support the dietitian in undertaking any analysis work.

Nutritional analysis

The declared values shall be average* values based on:

- the manufacturer’s analysis of the food

- a calculation from the known or average values of the ingredients used; or

- a calculation from generally established and accepted data (2).

* Average refers to figures which best represent the respective amounts of the nutrients which a given food contains, considering natural variability, seasonal variability, patterns of consumption and any other factor which may cause the actual amount to vary (3).

Chemical analysis

The manufacturer’s analysis of the food will be derived from chemical analysis, which is often used by the food industry for labelling purposes especially in products bearing health claims or declaring the content of vitamins and minerals and should not be established at either extreme of a defined tolerance range (3). Chemical analysis is also used by government bodies and in some research settings. It is an expensive procedure that must be undertaken by an accredited laboratory. A single analysis is only valid for that food item – grown, transported, stored, prepared and cooked under those specific conditions. The UK Food Databanks (4), which is the basis for nutritional analysis systems, is based on such chemical analysis.

Tolerances and rounding

It is not possible for foods to always contain the exact levels of energy and nutrients that are labelled, due to natural variations and variations from production and storage (3). Therefore tolerances for nutrient values declared on a food label are covered in official guidance in line with EU legislation (3). This guidance is outlined in Appendix 11.

Rounding guidelines have also been given regarding the number of significant figures or decimal places in order not to imply a level of precision which is not true. Appendix 12 contains the rounding guidelines for the nutrient declaration in nutrition labelling of foods.

Calculated analysis

Calculation for the nutritional values of recipes uses weights of ingredients and generally established and accepted food composition data. This is done using generic and manufacturers’ data and is the mostly widely used and accepted method in industry, schools and healthcare settings.

The nutritional data commonly used for calculation in the UK software includes McCance and Widdowson’s ‘The Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset (CoFID)’ (5). New searchable versions of McCance and Widdowson’s Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset are freely available, including The Quadram Institute’s Food Databanks (4) and Nutridex (6).

Standard recipes

Standard recipes must be followed to ensure consistency of quality, nutrition and allergen data as well as costs and safety of the food.

Recipe analysis

Recipe analysis can be carried out using an appropriate commercially developed nutritional analysis software package (see Table 8.6) or by using spreadsheets. While the latter is more cost effective, it can be more time consuming and prone to errors. Recipe analysis can be undertaken by experienced registered dietitians, registered nutritionists, or appropriately trained individuals under the supervision of a registered dietitian or nutritionist. The analyst should be able to interpret both the input data and the results and be aware of food regulations and the limitations of their software.

To produce a standard recipe and complete a full analysis the following information shown in Table 8.1 is required.

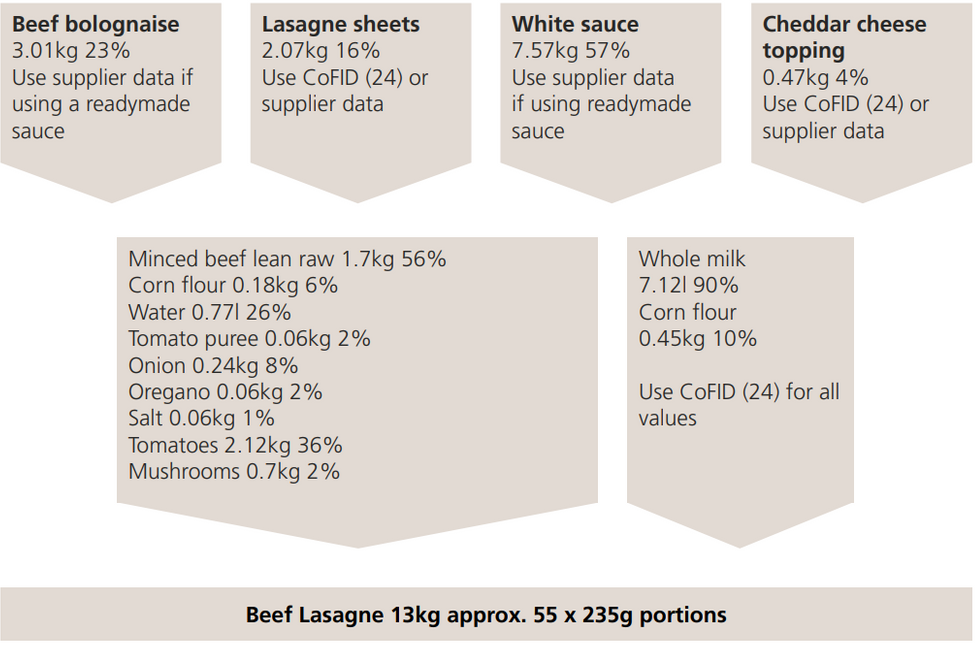

Each recipe component will need its own analysis (see Figure 8.1).

Table 8.1: Information for completing a recipe analysis

|

Information |

Details |

|---|---|

|

Recipe Code |

A code number that identifies the recipe. |

|

Recipe Name |

Each recipe must be given a unique identification and a descriptive title e.g., poached haddock with cheddar cheese sauce. |

|

Ingredients |

The full list of recipe ingredients, including fluid and seasoning. |

|

|

Clearly define each specific ingredient and/or brand in the recipe and ensure the corresponding ingredient from the dataset is selected e.g., milk either dried or fresh; whole; semi-skimmed, skimmed. In some analysis packages it is possible to input actual brand names for ingredients instead of looking up a corresponding ingredient from the CoFID (5) dataset. |

|

Weights |

All weights should be specific and given in metric units not household measures. |

|

|

Liquid content may need to be converted from volume to weight, based on individual specific gravities (7). |

|

|

Dry mixes and ingredients may need to be entered as dry weight with additional water in recipe or ‘as served’ weight, e.g., lentils, rice, pasta and soup powder. Some analysis packages will automatically convert dry to cooked weights of ingredients like pasta when analysing the final composition. |

|

Method |

Instructions for preparing and cooking – so the recipe can be replicated, including equipment and serving utensil details. |

|

|

Preparation methods need to be known - the edible portion weight e.g., the drained weight for canned foods, fruit and vegetables after peeling. |

|

|

Cooking methods need to be known e.g., frying, baking. |

|

Food Safety |

Hazard analysis critical control points (HACCP) should be documented e.g., cooking temperatures and times. |

|

Recipe Yields |

The relationship between batch size and portion yield should be established by testing the recipe or seeking advice from a knowledgeable chef. In a traditional kitchen, yields will vary slightly due to the natural variation in foods. It is important to consider the weight losses or gains during cooking e.g., water evaporation when calculating the recipe yield and portion weight. |

|

Portion Size |

Ensure the single portion size (volume or weight) for the recipe is appealing and nutritionally appropriate and give feedback to the recipe owner if this is not the case. The food portion size book may be useful for this (8). |

|

Nutritional Analysis |

The nutrient composition should be given per 100g and per portion. In traditional catering practice calculating per recipe or batch is likely to be the method used. Most nutritional analysis packages convert to 100g values but ensure that cooking losses and gains have been accounted for (see below). |

Further useful details on recipe development can be obtained from ‘Food in Hospitals: National catering and nutrition specification for food and fluid provision in hospitals in Scotland’ (9).

Methodological limitations

Cooking losses and gains can be significant and difficult to calculate. An assessment of cooking losses/gains is given in McCance and Widdowson’s ‘The Composition of Foods, Seventh Summary Edition’ (7). Most analysis software programmes can account for these losses or gains. It is important to take a pragmatic approach.

For the purposes of menu analysis, the loss may not be nutritionally significant. Examples of these are:

- Water loss during chill and frozen storage

- Water loss during reheating/regeneration

Where nutrient losses are significant this should be considered. Examples of these are:

- Fluid lost during baking of sponges or open cooking of meat or fish dishes. This results in a concentration of the nutrients (as only water is lost) and may affect the weight and portion size of the finished dish.

- Fat and water lost during grilling of meats and meat products.

Missing data

In the case of missing food composition data, suppliers can be contacted for this information. If this is not possible, then use of the closest match in the CoFID data set (5) is advised. CoFID data is likely to be preferable when specific nutrient data e.g., vitamins, is not available from the supplier. This data may be calculated or derived by chemical analysis and should still be checked in terms of reliability and compatibility. If the source of data is not McCance and Widdowson’s ‘The Composition of Foods, Seventh Summary Edition’ (7) or CoFID (5) it must be identified within the software dataset. Should an alternative database, such as the United States Department of Agriculture (UDSA) food data (10), be used to assess ‘missing values’, these must be clearly referenced.

Vitamin losses

Vitamin loss may be significant for heat-labile vitamins such as vitamin C, folate and thiamine. These can be assessed manually or through nutritional analysis software. In practice, menus should be designed to provide reliable sources of these less heat stable vitamins (see Chapter 9).

Cooking gains

When cooking in fat or water, these may be absorbed by the ingredient and any gains should be accounted for.

- Fat uptake during frying is very difficult to estimate e.g., fried potatoes. Fried values from CoFID (5) should be used where necessary. The cooked weight will need to be estimated if only the raw weight is known.

- Fat uptake for ingredients fried before incorporation into recipes needs to be included in the calculation for the final dish.

- Dry foods such as cereal, pasta, rice (as a starchy side option) and pulses will absorb water. Cooked values can be used if cooked weight is known. Uncooked pasta or rice (in a recipe) e.g., risotto or lasagne can be added as dry weight as they will absorb the fluid from other ingredients when cooking.

Recipe types

The approach to recipe calculation will differ depending on the type of dish. The following section provides a description of the methods used.

Simple recipes

These recipes are a simple addition of the analysis of each of the single ingredients listed (to include water), using data for either raw or cooked ingredients (state which) depending on the known weights in the recipe.

Cooking losses or gains are assessed, either by test weighing the finished product before and after cooking or by using data as supplied by CoFID (5). It is important to realise that variations in finished weight are inherent in traditional catering practices.

Composite recipes

These are multi-layered dishes composed of more than one recipe combined to form a composite. Calculate each part of the recipe as a simple recipe as described above and then create a recipe, which is the final make-up of the dish. An example of this is given for a beef lasagne recipe, see figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1: Example of Layered Dishes such as Beef Lasagne

Recipe analysis software

There are many different commercial nutritional analysis software packages available. When looking to purchase a software package or licence it is advisable to first determine the needs of the analyser and/or the organisation. Liaising with the catering department may be useful as some packages have functions that are suitable for both caterers as well as dietitians. It is advisable to make a detailed list of what you wish your recipe analysis software to do before you start looking at the available packages. Example considerations may include:

- Does the supplier regularly update the CoFID (5) dataset?

- Is it possible to add foods and recipes to the dataset and if so, how many and how much will this cost?

- Does the package provide a live link to the nutrition and allergen data of foods sold by large suppliers/manufacturers?

- Does the package allow for cooking losses or gains during analysis?

- Is the package able to print labels for foods (e.g., sandwiches / salads) including the ingredients, allergens and nutrition declaration?

- What other analysis would you like it to perform e.g., menu analysis, menu costing?

- Do you wish to combine the nutritional analysis function with catering functions such as the calculation of gross profit?

- What is the cost of a license per user, either annually or per month?

- Does the software company provide training or a guide to using the system?

- Does the software company provide on-going technical support, software updates and development and/or maintenance of the software system?

Examples of software that can be used to analyse recipes and menus are given in Table 8.2. The list is not exhaustive. It is presented in alphabetical order, and we do not endorse any particular system.

Table 8.2: Nutritional Analysis Software

|

Software System /Supplier |

Details |

|---|---|

|

A La Calc |

|

|

Delegate |

|

|

Dietplan 7 |

Forestfield Software Limited. http://www.foresoft.co.uk/ |

|

Kafoodle |

|

|

My Food 24 |

https://www.myfood24.org/professional-nutritional-analysis-software |

|

Nutmeg |

|

|

Nutridex |

https://www.nutridex.org.uk/ (free) |

|

Nutrimen |

|

|

Nutritics |

|

|

Nutrium |

|

|

Saffron |

|

|

Starchef |

Fourth Limited. https://www.starchef.net/ |

Food labelling legislation

Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of Food Information to Consumers (EU FIC) became law in 2011 (2). EU FIC brought European Union (EU) rules on general, and nutrition labelling together to simplify and consolidate existing legislation into one single regulation. Although the UK has left the EU, the EU FIC regulation has been retained in UK Food Law (11).

Nutrition information

Nutrition labelling on packaged foods

Commonly referred to as “back of pack” nutrition labelling, a nutrition declaration is mandatory under EU FIC for all packaged food products, regardless of whether a nutrition or health claim is made. The mandatory declaration comprises of the seven nutrients as shown in Table 8.3; therefore all food suppliers must be able to provide this information (2).

Table 8.3: Order of Seven Mandatory Nutrients under EU FIC (except annex V exceptions)

|

Nutrient |

Units |

Useful Calculations |

|---|---|---|

|

Energy |

kJ |

kJ (F x 37) + (CHO x 17) + (P x 17) + (fibre x 8) |

|

kcal |

kcal (F x 9) + (CHO x 4) + (P x 4) + (fibre x 2) kcal x 4.2 = kJ |

|

|

Fat (F) |

g |

|

|

of which saturates |

g |

|

|

Carbohydrate (CHO) |

g |

|

|

of which sugars |

g |

|

|

Protein (P) |

g |

|

|

Salt |

g |

Sodium (g) x 2.5 |

Supplementary Nutrients

Under article 30 of EU FIC (2) the mandatory nutrition may be supplemented (voluntary) with one or more of the following:

- mono-unsaturates

- polyunsaturates

- polyols

- starch

- fibre

- any specified vitamins or minerals present in significant amounts.

If a nutrition or health claim regarding any of the supplementary nutrients is made, the nutrient must be included in the nutrition declaration.

This mandatory information includes the important nutrients needed for menu planning and analysis. Where some relevant micronutrient data is unavailable but needed for therapeutic diets (e.g., potassium for patients with renal disease), the dietitian may be able to access the information direct from the manufacturer if available or use ingredient lists (full ingredient lists are mandatory under EU FIC). An ingredient list could be used to identify good or poor sources of micronutrients as this is generally the basis of advice given to patients. Ingredient lists are ordered in descending order of volume included.

Any ingredients listed in the title of the food or drink product must and for key have quantitative declaration giving the percentage present in the product (e.g., a pork sausage must list the percentage of pork meat present in the sausage in the ingredients list). McCance and Widdowson’s ‘Composition of Foods Integrated Dataset (CoFID)’ (5) can also be used for guidance.

There is no requirement for nutrition information to be provided for food sold unpackaged, however in healthcare catering settings this information is often provided voluntarily to support dietitians in the clinical or public health setting and used for menu planning and dietary coding. In this case the information must meet the requirements set out in the EU FIC (2), namely:

- Energy value (both kJ and kcal) only

- Energy value (both kJ and kcal) + 4 (fat (g), saturates (g), sugars (g) and salt (g))

- Its provision must meet legibility and font size requirements

This information can be provided:

- per 100g/ml only

- per 100g/ml and per portion or

- on a per portion basis only (applies only in the case of energy + 4)

Front of Pack Nutrition Labelling (12) also includes:

- Where information is provided per portion only for the four nutrients (energy + 4), the absolute value for energy must be provided per 100g/ml in addition to per portion (there is no requirement to express per 100g/ml for non-prepacked foods)

- Percentage reference intakes (RI) can be given on a per 100g/ml and/or per portion basis

- Where % RI information is provided on a per 100g/ml basis, the statement ‘Reference intake of an average adult (8400kJ/2000kcal)’ is required

- Additional forms of expression are allowed if they meet requirements set out in the EU FIC

Voluntary front of pack nutrition labelling cannot be given in isolation; it must be provided in addition to the full mandatory (“back of pack”) nutrition declaration. This is energy value (both kJ and kcal) + fat (g), saturates (g), carbohydrate (g), sugars (g), protein (g) and salt (g) (12).

Allergen information

The declaration of the 14 allergens

It is a mandatory requirement for 14 allergens, identified by the EU as most likely to cause harm, to be made known to consumers buying any prepacked or non-prepacked food and/or drink item. The 14 allergens listed in the legislation are: cereals containing gluten (namely wheat (such as spelt, Khorosan wheat/Kamut) oats, rye and barley); crustaceans; eggs; fish; peanuts; soya; milk; nuts (almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, cashews, pecan, brazil nuts, pistachio, macadamia); celery; mustard; sesame seeds; sulphur dioxide; lupin; molluscs (2).

Natasha’s Law

On 1 October 2021 Natasha’s Law (13) came into force in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. As a result, any business that produces food pre-packed for direct sale (PPDS) is required to label the food item with a full list of ingredients and the allergens. PPDS foods are items that are packaged in the same place they are being offered or sold to consumers and are in this packaging before they are ordered. For non-prepacked food there is some flexibility to how the information can be provided.

For food service in healthcare settings, if any products are packaged onsite, they must be opened before being served to a patient or must have a label with all the ingredients present, and allergens highlighted. Typically, these products may include decanted toppings for jacket potatoes (e.g., grated cheese), potted sides (e.g., potato salad) and pre-packaged sandwiches and salads made onsite.

In line with legislation, allergen information must be readily available on each ward. This may be an up-to-date allergen file and/or digital allergen information for all menu items.

Further allergen guidance for food businesses can be found on the Food Standards Agency website (14) and in Chapter 6 of this document.

Click here to go to the next chapter.

Click here to return to the top of the page.

References

- NHS England. National standards for healthcare food and drink. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-standards-for-healthcare-food-and-drink/ [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Legislation.gov.uk. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eur/2011/1169/contents# [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- European Commission Health and Consumer Directorate-General (EC). Guidance document for competent authorities for the control of compliance with EU legislation on Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 with regard to the setting of tolerances for nutrient values declared on a label. https://www.fsai.ie/uploadedFiles/guidance_tolerances_december_2012.pdf [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- The Quadram Institute. Food databanks. https://fdnc.quadram.ac.uk/ [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Public Health England. Composition of foods integrated dataset (CoFID). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/composition-of-foods-integrated-dataset-cofid [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Nutridex. Nutridex. https://www.nutridex.org.uk/ [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Finglas PM, Roe MA, Ounchen HM, Berry R, Church SM, Dodhia SK, Farron-Wilson M. & Swan G. McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods, Seventh Summary Edition. Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2015.

- Mills A & Patel S. Food Portion Sizes. Third Edition. London: Food Standards Agency; 2002.

- The Scottish Government. Food in Hospitals: National catering and nutrition specification for food and fluid provision in hospitals in Scotland. https://www.nss.nhs.scot/publications/food-in-hospitals-shfn-04-01/ [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. FoodData Central. https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Food Standards Agency. General food law. https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/general-food-law [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Department of Health and Social Care. Technical guidance on nutrition labelling. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/technical-guidance-on-nutrition-labelling [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Food Standards Agency. Allergen labelling changes for prepacked for direct sale (PPDS) food. https://www.food.gov.uk/allergen-labelling-changes-for-prepacked-for-direct-sale-ppds-food [Accessed 20th March 2023]

- Food Standards Agency. Allergen guidance for food businesses. https://www.food.gov.uk/business-guidance/allergen-guidance-for-food-businesses [Accessed 20th March 2023]